Despite more than a century of research, blood science remains an unfinished map. Doctors may appear to have fully charted it, with ABO and Rh types dominating medical conversations, yet reality is far more complex. Transfusion specialists know there are hundreds of antigens, many still poorly understood. Occasionally, unexplained reactions occur that puzzle clinicians and scientists alike.

These rare cases are important reminders: the human body continues to surprise even in its most well‑studied systems. Behind every transfusion is a reality of risk, a chance that something hidden lies beneath the surface.

Why Compatibility Matters

Blood transfusion is one of medicine’s most common and lifesaving procedures, yet it requires extraordinary care. A mismatch between donor and recipient blood can trigger fatal immune reactions. The World Health Organization records over 100 million donations worldwide yearly, most used safely. However, compatibility extends beyond the familiar ABO and Rh systems.

Overlooked antigens can still cause devastating complications. For individuals needing repeated transfusions or pregnant women carrying affected fetuses, even a hidden mismatch is catastrophic. This is why researchers keep exploring blood diversity—to ensure no patient slips through gaps in scientific understanding.

Beyond Group A, B, and O

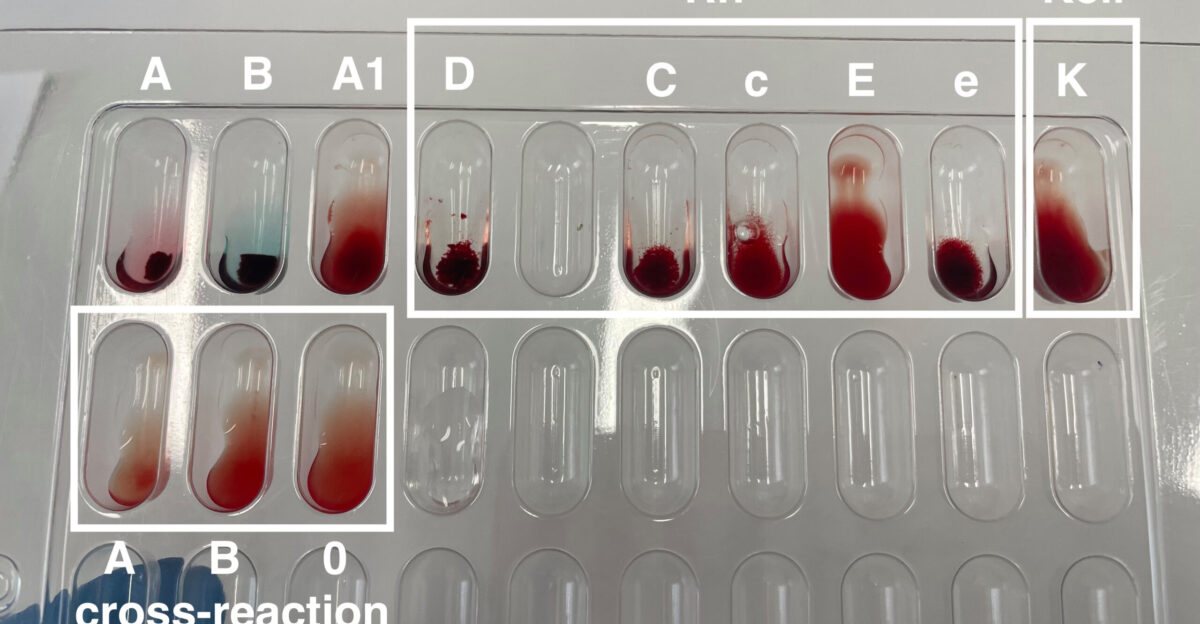

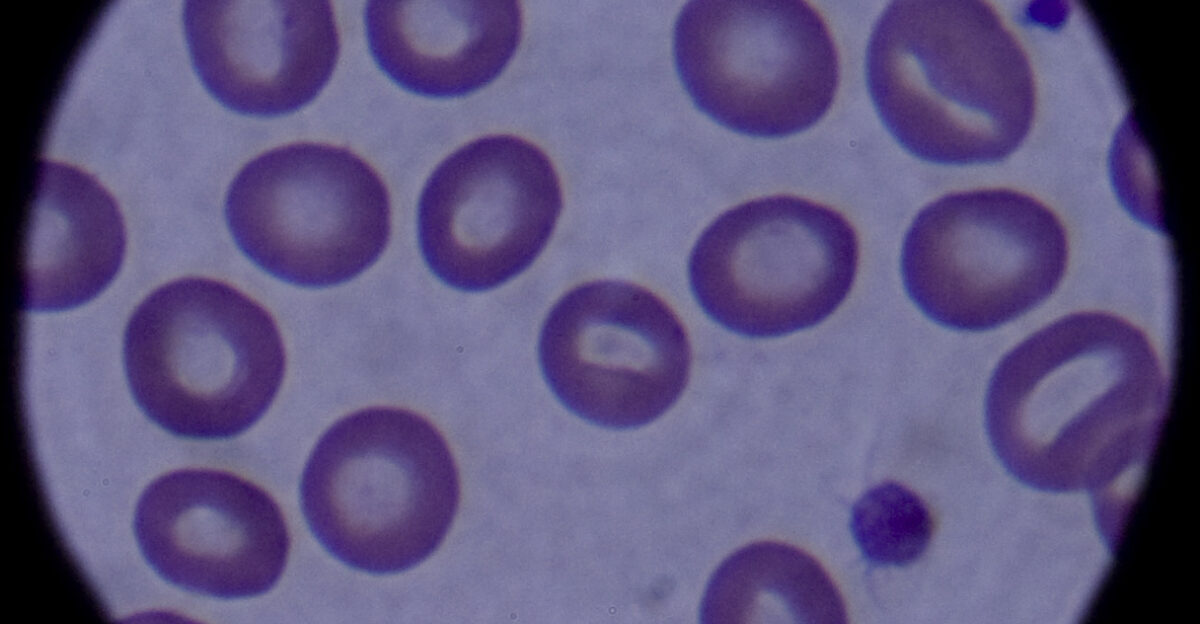

Most patients only hear about eight standard categories: A, B, AB, or O, each positive or negative. In actual transfusion science, however, the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) documents far more. At least 360 antigens across dozens of systems make up the full picture of human blood differences.

Duffy and Kidd are rare yet profoundly important in niche cases. The discovery of these hidden systems has consistently improved safety, reducing unexplained deaths. Still, laboratories detect mysterious patterns that don’t align with the established map, raising questions science cannot yet answer.

The Invisible Threat in Pregnancies

Pregnancy provides a dramatic example of hidden blood incompatibility. If a mother’s immune system detects foreign blood antigens from her baby, it can attack the fetus’s red cells. This condition, hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN), once caused many infant deaths. Interventions like Rh immunoglobulin injections now prevent the most common forms.

Obstetricians, however, still encounter rare cases where known antibodies cannot explain the damage. These tragic cases reveal that our catalogue of antigens remains incomplete. For decades, scattered reports suggested hidden blood factors might be involved, but answers often remained elusive.

How Clues Accumulate Over Time

Blood group science advances incrementally. For example, ABO was solved in 1900 following unexplained transfusion failures. The Rh system came to light during the 1940s, after doctors noticed pregnancy complications among Rh‑negative women. Dozens of additional systems were added throughout the 20th century, usually when clinical anomalies forced investigation.

This pattern continues today, as each puzzling case emerges, scientists probe with new tools, and the field recognizes that another antigen system exists. Despite expensive technology, progress still depends on rare, sometimes tragic, patient experiences, which provide the puzzle pieces that unlock new classifications.

The Role of International Standards

When anomalies arise, laboratories cannot classify new systems in isolation. They rely on the Geneva‑based International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT), which governs naming and numbering. Once sufficient clinical and genetic evidence is gathered, ISBT formally adds a newly confirmed blood group to the international registry.

Today, 48 recognized systems exist, but only after years of careful validation. Each addition represents not just discovery, but also the establishment of protocols to guide blood banks, register rare donors, and inform clinical practice worldwide in both transfusion and obstetric medicine.

Mysterious Reactions in Real Patients

In hospital wards, patients sometimes present transfusion reactions clinicians cannot explain. Blood appears perfectly matched under ABO and Rh typing, yet antibodies attack donor red cells unexpectedly. These episodes prompt deeper testing. For years, specialists have collected such rare cases, often involving women with pregnancy complications or chronically transfused patients.

Each incident made doctors feel that something important was missing in their medical dictionaries. Such unexplained reactions became the starting point for investigations that would ultimately reveal one of the rarest blood group systems yet identified, setting a new milestone in hematology.

An Exceptional Patient Emerges

Among these mysterious cases, one stood out. A woman living on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, a French territory, displayed blood patterns unlike any scientists had seen. Routine tests repeatedly failed to classify her results. When clinicians exposed her blood to panels of antibodies, reactions appeared inconsistent with every known system.

For medical teams, the anomaly suggested a silent factor not previously recognized. Researchers from France and Europe soon joined efforts to investigate further. What began as a local puzzle surrounding a single patient gradually set the stage for a global scientific breakthrough.

The Laboratory Mystery Deepens

Detailed testing showed that her red cells lacked a specific antigen present in virtually everyone else. When exposure occurred, antibodies developed in her system attacked this absent antigen. Yet researchers couldn’t match it to any known group. Traditional serology had no answers. Scientists, therefore, turned to modern sequencing, mapping the proteins shaping her red blood cells.

The results confirmed suspicions that she carried a previously undocumented blood profile. For the first time, the absence of a high‑frequency antigen could be fully explained. This single case provided hard genetic evidence of a hidden system.

A Breakthrough in Science

Genetic studies revealed the woman was negative for a molecule nearly universal in other humans. Researchers realized they were confronting not just a variant but an entirely new blood group system. Evidence was presented internationally, combining detailed laboratory reactions, family studies, and molecular sequencing. The case satisfied all ISBT criteria for recognition.

The puzzle offered clinicians and scientists rare satisfaction: after years of unexplained clinical reactions, they had found a scientific explanation. After rigorous review, the once stray laboratory anomaly evolved into an internationally recognized addition to human blood group science.

The Reveal of the GW System

In 2025, the ISBT officially designated the GW blood group system, marking the 48th recognized system in humans. Its defining feature is a single high‑frequency antigen called GW(a), also nicknamed GWADA, a nod to its discovery in Guadeloupe. The Guadeloupe woman is the only confirmed GW(a)‑negative person in the world.

In blood group terms, this makes her phenotype extraordinarily rare. Though one patient revealed it, GW’s recognition affects everyone, adding a new layer to transfusion safety frameworks and reminding medicine how uncharted regions remain, even within familiar human physiology.

The Rarity of GW(a)‑Negative Blood

The woman’s blood represents uniqueness on a global scale. Because nearly the entire human population carries GW(a), identifying someone lacking it is scientifically remarkable. For her personally, this creates profound challenges. If she needs a transfusion, compatible blood would likely be impossible to find outside her own donations.

For transfusion medicine, it highlights the unavoidable unpredictability doctors face. At the same time, her case is invaluable. Her unique blood forms the reference standard by which new laboratory reagents are tested, enabling global clinics to identify and protect other rare patients.

Why GW Matters Clinically

Like Rh or Kidd before it, GW antigens can pose risks in two major contexts, namely that of transfusion and pregnancy. If a GW(a)‑negative patient develops antibodies after exposure, transfused red cells carrying GW(a) could be destroyed, a complication known as hemolytic transfusion reaction.

Similarly, if a GW(a)‑negative mother carries a GW(a)‑positive fetus, antibodies may cross the placenta and cause HDFN. Recognition of GW ensures these rare but severe risks will be diagnosed accurately in the future. With it, transfusion science can prevent tragedies by acknowledging an incompatibility that previously existed silently.

Expanding the Blood Safety Net

Each new blood group expands the healthcare system’s ability to safeguard patients. The GW discovery guarantees that when unexpected cases arise, clinicians now have official guidance and language to explain them. While it may take years for routine screening to include GW, awareness has already changed practice.

High‑risk pregnancies can be evaluated for GW antibodies, and blood banks can begin planning for potential GW‑negative donor identification. Just as Rh discovery revolutionized obstetrics, GW adds another guardrail. Even if rare, its recognition builds a more comprehensive, resilient transfusion medicine landscape worldwide.

Technology Enabling New Discoveries

GW could not have been recognized without 21st‑century technology. Traditional blood typing relies on visible reactions: A reaction appears when an antigen meets an antibody. But high‑frequency antigens like GW(a) rarely reveal themselves this way. Genomic sequencing, coupled with protein biochemistry, provided the breakthrough.

By decoding the exact genetic difference in the Guadeloupe woman’s DNA, scientists uncovered why her red cells lacked GW(a). This integration of classical immunology and modern genetics illustrates the shifting medical frontier. Cutting‑edge laboratories now treat the genome as a map, constantly scanned for clues hidden beyond the microscope.

Global Collaboration in Action

The GWADA discovery was not the achievement of a single institution. Researchers in Guadeloupe, France, and across Europe collaborated to verify findings and satisfy ISBT criteria. Samples were shared internationally. Peer‑reviewed papers pooled genetic and serological evidence. ISBT specialists validated results before formally numbering GW as the 48th system.

Such collaboration shows the scale of modern transfusion medicine: rare discoveries require global teamwork. A single patient’s sample on a Caribbean island ultimately reshaped textbook knowledge in Geneva, Europe, and beyond, reinforcing how interconnected networks make even the rarest discoveries possible.

Rare Donors and Registry Challenges

At present, there is only one known GW(a)‑negative donor, the woman from Guadeloupe. Global blood networks face a daunting challenge should she require a transfusion. This reality highlights the importance of international rare donor registries, which already track individuals with unusual profiles in case lifesaving blood is needed.

As more GW research unfolds, donor banks may seek to identify potential carriers worldwide. Though the discovery of another GW(a)‑negative individual is unlikely soon, expanding registries and encouraging donation diversity ensure that even anomalies can be supported when medicine is tested most severely.

Evolutionary and Biological Questions

Why is GW(a) so universal? Scientists suspect high‑frequency antigens often persist because they provide evolutionary advantages or have no harmful effects. Many blood group variations correlate with disease resistance: the Duffy system, for example, influences vulnerability to malaria. Whether GW has a similar role remains unknown.

The fact that the Guadeloupe woman survives normally despite lacking GW(a) suggests the antigen is not essential for life, but its near‑universal presence implies some hidden evolutionary story. Investigating GW could therefore shed light beyond transfusion safety, broadening knowledge of human biology and survival.

One Woman’s Global Impact

Although the Guadeloupe woman remains anonymous, her story highlights how a single life can influence global medicine. What makes her unique is also what extends her legacy, that without her contribution, the GW blood group system might still be hidden. For patients worldwide, her case translates into improved diagnostic capacity, fewer unexplained transfusion reactions, and better outcomes for families facing rare pregnancy complications.

Her medical rarity reshaped an international classification. This illustrates medicine’s paradox that even the rarest patient can hold the key to protecting many, their uniqueness transforming into collective safety.

The Continuing Journey of Discovery

The official recognition of the GW blood group system as the 48th in humans marks a significant moment in transfusion science. It again proves that even seemingly familiar aspects of biology hold hidden depths. GW adds a safeguard for future patients, ensures better maternal‑fetal care, and reinforces the value of global cooperation.

From ABO to GW, every discovery has reshaped expectations about safety and compatibility. For healthcare, the lesson is clear: science must remain open to new findings. Medicine discovered another powerful reminder in one woman’s blood that knowledge is never complete.